The Puzzle of Psychological Safety

Julian Waters-Lynch

When does psychological safety help and when does it hinder team performance?

10-Second Summary

Teams with a strong sense of psychological safety feel more comfortable speaking up, debating decisions and taking risks , all of which can help promote learning, innovation and improve performance.

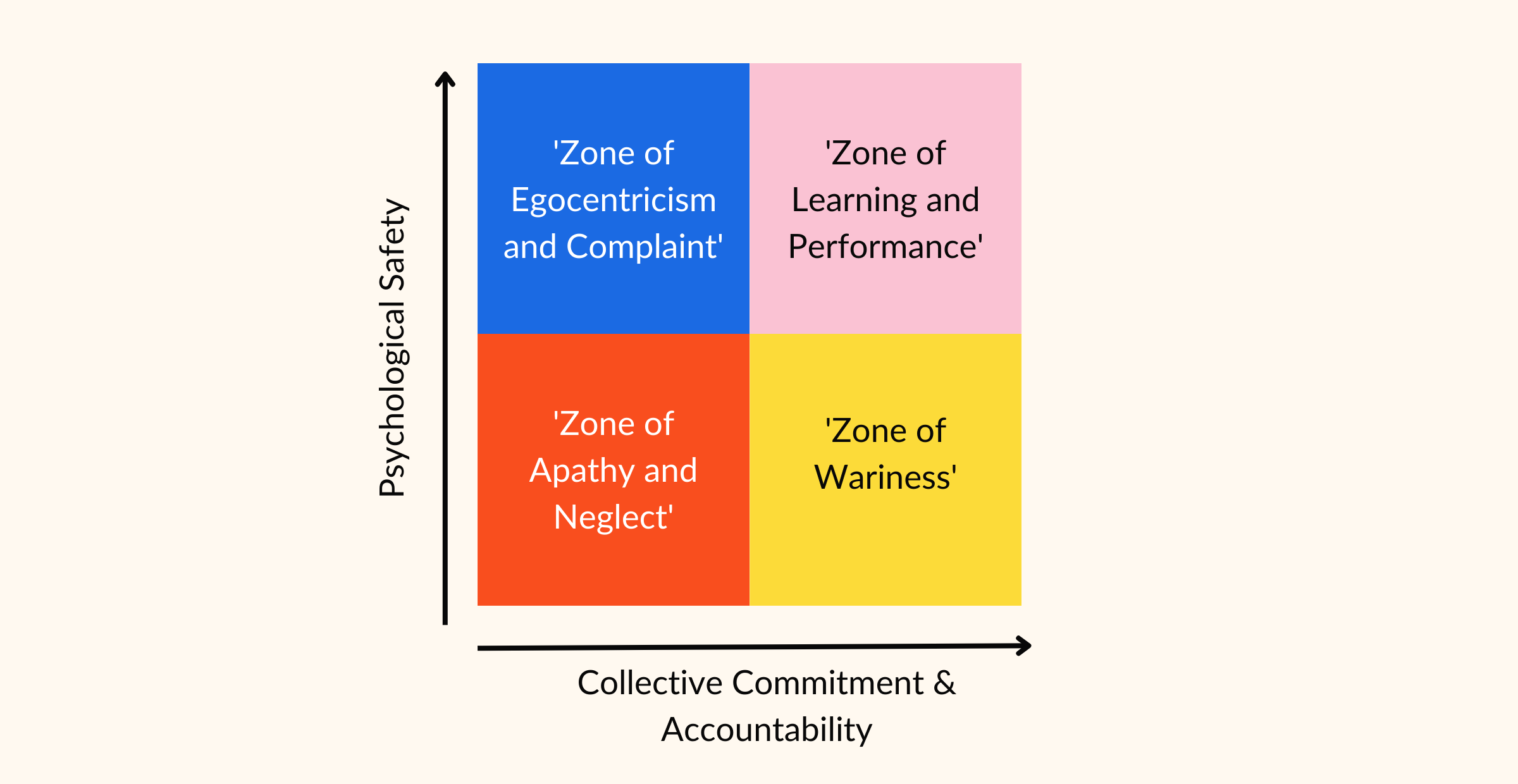

But to have this effect, psychological safety must be coupled with a strongly felt sense of accountability and collective commitment to the team’s goals, otherwise it can have a negative effect on team performance.

Leaders and team members should balance a healthy sense of psychological safety with a felt sense of accountability and norms of collective commitment towards shared goals in order to build a culture of high performance.

Safety is a good thing, right? In the workplace, psychological safety has become a popular concept among many leaders and consultants. This view builds on the research and advocacy of Amy Edmondson, who has long argued that psychological safety is a key determinant of high performing teams, especially with regard to learning and innovation. Given this, it would be easy to think of psychological safety as an unqualified good, where the safer a team feels with each other the better.

But recent research has challenged this simple story. These findings explore the potentially darkside of psychological safety, and help distinguish the conditions under which it is helpful for teams, from situations where it is neutral or can even hinder performance.

What is psychological safety and how does it help team performance?

First of all let’s review what’s meant by psychological safety and how it is thought to help team performance. Psychological safety is usually defined as a shared belief held by members of a team that the team is safe for interpersonal-risk taking. Researchers tend to measure it through questions such as ‘if you make a mistake in this team, to what extent is it held against you?’ and ‘how difficult is it to ask other members of this group for help?’.

Amy Edmondson has argued that psychologically safe teams learn more effectively, especially when they are more comfortable in acknowledging and analysing past failures. Learning is also a key component of innovation, and psychologically safe teams are said to propose more unconventional ideas, and consider minority views with less fear of negative judgement from others. These links between risk, failure and learning make sense, given innovation involves taking risks and backing ideas that are uncertain and often result in failure. As Edmondson puts it:

These claims were given a popular boost in 2012 through Google’s (now Alphabet) Project Aristotle. This was impressive research conducted by their people analytics team to discover the factors that have the greatest influence on effective teams. After analysing 180 teams for over a year, they were surprised to find a range of their initial hypotheses didn't appear to have much effect on team performance. Factors such as co-location, decision-making approaches, the performance or psychological traits of individual members, workload and team size, seniority or tenure did not appear to significantly predict team performance. (Of course, Google is only a single, and quite unusual organisation, and the research team acknowledged some of these factors might have greater effect in other organisations).

By contrast, the five factors that appeared to most significantly predict team effectiveness were identified as:

Psychological Safety: that team members feel safe to take risks and be vulnerable in front of each other

Dependability: team members get things done on time and meet a high bar for excellence

Structure and Clarity: team members have clear roles, plans, and goals

Meaning: work is personally important to team members

Impact: team members think their work matters and creates change.

Of these five, psychological safety became popularly seen as the most important determinant of highly performing teams. A second aspect that caught attention was the finding that the norms among teams and quality of group interactions appeared to matter much more than the characteristics and performance of individual team members. At least at Google, it seems a champion team outperformed a team of champions.

Two team behaviours in particular were identified as critical to fostering a climate of psychological safety: equality of conversational turn-taking and active listening. So a common take-away from this research is that if you want to strengthen the sense of psychological safety within a team, you should pay close attention to the degree of equality in speaking time among members and the quality of attention with which they listen and question each other.

Collective commitment and felt accountability as neglected ingredients of team success

So far so good, so let’s thicken the plot a little.

Two recent papers have provided new evidence that higher levels of psychological safety don’t always improve team performance. The key insight they demonstrate involves identifying what other ingredients are necessary for psychological safety to improve the recipe of team success. These papers help flesh out what researchers call the ‘boundary conditions’ of psychological safety, or questions regarding when, where and for who does it help.

The first paper, Slacking off in comfort: a dual-pathway model for psychological safety climate, surveyed 80 teams consisting of 247 employees and then attempted to replicate the survey in a controlled experiment with 288 university students placed into 96 teams. The authors found that higher levels of psychological safety could be associated with positive or negative impact on team performance (measured in this case through group risk taking behaviour and creative output) depending on the presence of a third factor. What is this mysterious extra ingredient? Well, in this paper they also measured group norms, specifically the degree to which work groups were individualist or collectivist in their orientation.

Individualist oriented groups are more likely to pursue personal goals and achievement and place less importance on interpersonal harmony among members, or the superordinate goals of the team itself. Collectivist oriented groups are more likely to place the group’s goals above their own needs, which also tends to coincide with strong social connections with others in the group. For individualist oriented groups, they concluded:

“A psychologically safe climate is likely to lead to a significant loss of work motivation when group members are lukewarm about group success”

In other words, strengthening the psychological safety of a team does lead to the positive effects described by Edmondson and others, but only when accompanied by other elements such as strong sense of collective commitment and accountability to the group. In more individualist oriented groups, with a weak sense of interdependence and mutual accountability, simply increasing the sense of safety can actually reduce group motivation and see performance deteriorate, as members become more comfortable slacking off.

A similar conclusion was reached by the second paper. The authors of When is psychological safety helpful in organizations? A longitudinal study studied 170,000 survey responses in 545 schools over three years to construct a robust analysis of the boundary conditions of psychological safety. This time they explored the relationship between psychological safety and felt accountability. Accountability is the expectation that one’s decision or actions will be subject to evaluation by a salient audience, which can include oneself, team members or the larger organisation. They expected to find a positive association between psychological safety and school performance over time. But they actually found that schools with a high sense of accountability, and moderate levels of psychological safety were the most successful in meeting their performance targets over time

The authors suggest that a strong sense of accountability helps focus energy and attention on specific team and organisational goals, and under these conditions, psychological safety can act as a catalyst that helps widen the space for constructive debate and exploring novel solutions to problems.

“In our study psychological safety acted like a ‘pinch of yeast’ - a small dose that acted as a catalyst to amplify the positive effects of accountability on team performance”

But measured on its own, psychological safety had no significant effect on performance.

What does this mean for teams and leaders?

So, after all of this, is psychological safety a good thing or not? The answer is it depends on some other conditions that a team or organisation might exhibit. We need to proceed thoughtfully in diagnosing what a particular team needs more or less of when seeking to improve its performance.

Of course accountability has a darkside too. Too strong a sense of accountability, especially when coupled with autocratic leadership can create highly anxious and risk-adverse team climates that make it difficult to learn, innovate or even sustain high performance overtime. It also usually sucks to be part of these environments.

Some teams and organisations can absolutely benefit from increasing the sense of psychological safety, but these are more likely to be teams with a healthy sense of collective commitment and accountability towards shared goals. For other teams, performance is more likely to be improved through strengthening mutual commitment and accountability.

The challenge for leaders and team members is to appropriately diagnose the context you’re in, and learn to adjust the hot and cold taps of accountability and safety until the temperature is optimal.

Stay tuned for our upcoming podcast on this topic, where we’ll discuss ways to get the temperature ‘just right’.